ABSTRACT

Background: India has shown remarkable progress on several health parameters and a political will to usher in Universal Health Coverage (UHC) framework as defined by the global sustainable development goal 3.8. Given myriad challenges of a fast-growing economy with a massive population, how India fares on this goal is important not just for the country but also has implications at the global level. This research is a comparative analysis of progress made by India towards UHC vs. peer economies from BRICS and ASEAN-5. Materials and Methods: Three performance indicators were selected through a comprehensive review of research in the area, namely SCI (Service Coverage Index) for “access”, HAQ (Health Access and Quality) for “outcome”, and UHC index for a composite indicator of “access and financial protection”. In addition, financial protection parameters of out-of-pocket expenditures and consequent impoverishment were also considered. These indices measure distinct aspect of UHC, but none covers the full spectrum of success criteria, hence we used cross-tabulation technique for a holistic comparison. Results: Despite significant progress on various health indicators, India lags behind its peer economies of BRICS and ASEAN-5 in achieving UHC goal. A deficit in infrastructure and trained health-workforce continues to undermine efforts to provide healthcare to all, complicated further by inequitable distribution of these resources. Conclusion: Pharmacists have an important role in improving access to healthcare by playing a more active role in preventative care, patient counselling and disease management, thus supporting India’s ambitious journey towards achieving UHC for its over 1.3 billion citizens.

INTRODUCTION

Achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by 2030 is a commitment of the global community enshrined in Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted by 193 countries in 2015. The commitment was reaffirmed in 2019 when WHO’s thirteenth General Programme of Work 2019-2023 (GPW13) adopted the goal of 1 billion more people benefitting from universal health coverage by 2025 within its “triple billion” goals.1 The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically demonstrated to the entire world, the invaluable role of healthcare coverage and the importance of expanding investments in UHC.

According to the World Health Organization, UHC means that all people and communities can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship. UHC has been defined as a target in itself, as expressed in SDG 3.8, but quite obviously it is also an undeniable means to ensure achievement of all other health-related SDG targets.2 The WHO definition of UHC embodies three related objectives, i.e., equity in access to health services, high quality of health services and protection against financial risk ensuring that cost of these services does not put people at the risk of financial harm.

Consequently, two indicators were adopted by the UN Statistical Commission in March 2017 to monitor progress towards SDG target 3.8 on UHC, which are 1). The coverage of essential health services (SDG indicator 3.8.1) and 2). The proportion of households with large expenditures on health as a share of total household consumption or income (SDG indicator 3.8.2).3,4 By adopting these indicators, it was recognized that a concerted effort for improving these indicators can go a long way in uplifting the health status of populations and thus contribute to sustainable economic development. Indeed, the global performance on the UHC effective coverage index has significantly improved from 45·8 in 1990 to 60·3 in 2019. However, success of different countries in designing and implementing policies and their on-the-ground execution has been quite heterogenous, manifested in their disparate progress on these indicators.

India lifted over 271 million people out of poverty from 2005-2006 to 2015-2016 and another 180 million by 2021, drastically reducing the percentage population living with multidimensional poverty from 55.1% in 2005-2006 to 27.9% in 2015-16 and further to 6% in 2021.5,6 Although the proportion is still higher than other comparator countries,5 the progress towards this direction has been tremendous which is expected to positively impact spend on healthcare.

As India continues its journey being one of the growth engines of the global economy and with shrinking poverty levels, one would expect to see mirroring trends in the healthcare scenario as well. Over the last few decades, India has indeed made significant progress on the primary healthcare front. Life expectancy at birth has risen from 62·5 years in 2000, to 69.9 years in 2020.7 In 2020, the infant mortality rate was 27 per 1000 livebirths, less than half of that in the year 2000.8 Between 2000 and 2017, the maternal mortality ratio fell from 370 per 100,000 livebirths to 145 per 100,000 livebirths.9 The spread of HIV/AIDS has been contained,10 the country was declared polio free11 in March 2014 and free of maternal and neonatal tetanus in August 2015.12 Despite these appreciable gains, India is still quite far from achieving universal healthcare goal for sustainable development. Significant importance has been given for facilitating maternal and neonatal care to reach the last mile recipient but India still accounts for 22% of all the neonatal deaths and 18% of all infant mortality in the world.13 The age-standardised DALY rate in India dropped by 36% from 1990 to 2016, indicating overall progress in reducing disease burden, though this gain has been accompanied by a pattern of epidemiological transition to non-communicable diseases that now contribute to about 55% of all disease burden in India and more than 60% of deaths.14 Overall, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, haemorrhagic stroke, and diabetes are among the leading Non-communicable causes of the burden of disease, while infectious disease still remains a continuing battle. This changing disease demography is also a challenge that the country needs to overcome on its path to achieve universal health coverage. Pharmacists by their proximity to the community, can play an important role in reducing the burden of NCDs for the country. Better disease management and adherence to therapy can also reduce the overall financial burden on the patients. Awareness of the UHC targets and how the country is tracking against the set goals, will help the pharmacists prepare towards playing a proactive role in this pursuit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This paper attempts to highlight the progress of India and its peer economies towards achieving the goal of UHC, based on regional and country level indicators and relevant indices. Specifically, two blocks of countries have been chosen for this comparison-BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) which have been traditionally considered the growth driver emerging economies of the world and ASEAN-5 (Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines), the group of five key economies in South-East Asia. Three indices and related performance indicators were chosen through a comprehensive review of research studies conducted in the area, namely the SCI Index (Service Coverage Index)2 that measures “access” to healthcare and its quality, the HAQ (Health Access and Quality)15 that measures “outcome” and the UHC index4 that combines “access and financial protection” into a composite index. In addition, the financial protection parameters of out-of-pocket expenditures and consequent impoverishment were also considered for comparative analysis.

UHC Service Coverage Index (SCI) has been used as an official measure for SDG 3.8.1 and is a good indicator to measures “access” to essential health services based on 14 tracer indicators including reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, infectious diseases, Non-communicable diseases, and service capacity and access.2 Another index that has been used for measuring the quality of service is Healthcare Access and Quality (HAQ) index created by the Global Burden of Disease study.15 This index measures the performance of various countries on 32 preventable causes of mortality, from which death should not occur in the presence of effective care. While SCI is the index that measure access and quality of healthcare services and thus a lead indicator, HAQ is more of a lag indicator assessing the actual “outcome” in terms of preventable mortality still existing in the countries and hence quality of healthcare. Hence, countries with rigorous focus on SCI will eventually witness an improvement in preventable mortality, thus improving HAQ over time though with a lag.

The third selected index for measuring the progress, the UHC index is a composite measure of both the access and the financial protection aspects of UHC.4 Financial protection was measured using a single indicator of catastrophic health expenditure >10% of income, while service coverage index measurement included parameters for both service delivery of preventive healthcare and treatment access. Unlike the earlier described indices of SCI and HAQ, service coverage here neither included health outcomes data nor did it include the upstream influencing parameters such as health policy or health infrastructure.

All these indices provide important insights into the progress a country is making towards achieving UHC but at the same time each is limited in its scope and focus. Cross-tabulation of performance indicators is used as a simple yet powerful tool to analyse the comparative performance as different indicators cover distinct aspect and no one indicator comprehensively covers all aspects.

RESULTS

Performance on the Access and Quality Dimension of UHC

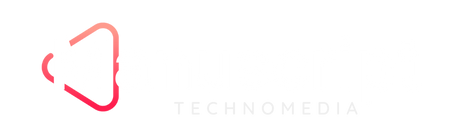

Service Coverage Index (SCI) is presented on a scale of 0 to 100, higher scores indicate better performance and countries having values greater than 80 on this scale are considered to have good coverage, with Canada at the top of the list with an SCI score of 89.2 Hence Canada is used as a benchmark country for comparison of all parameters in this paper. While Brazil, Russia and China among BRICs and Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia among ASEAN-5 are very close to UHC index value of 80, India is still far behind not just the developed world, but also all countries in the BRICS and ASEAN-5 as well as world average of 65.7 [Figure 1a]. Overall, India ranked 131 among 183 countries assessed for SCI. This is a stark contrast to the GDP rank where India is the fifth largest. There is though, a degree of a consonance between GDP per capita rank and SCI rank for India as also for other countries evaluated in this study, except for Brazil, China and Thailand that fare much better on health coverage than per capita GDP rank. Since there is a direct relationship between general well-being of a population and its financial well-being, the gains made in UHC can be expected to reflect in sustainable economic development.

Figure 1.

Comparison of India with other BRICS and ASEAN-5 countries on a) SCI Score, b) UHC Index Score c) HAQ Score and d) Rank comparison.

Note: Country rank based on evaluation of 183 countries for SCI score, 195 countries for HAQ score, 111 countries for UHC Score and 196 countries for GDP; Canada is included as the benchmark for comparison, being the top rank country for official SCI index

On HAQ index, India ranks 145 among 195 countries assessed,15 lagging BRICS and ASEAN-5 countries. However, there has been a continuous improvement over time with the HAQ score of 41.2 for India in 2016 being a 16.5-point improvement in 26 years [Figure 1c]. India is plagued by large disparities at subnational level. A 30·8-point disparity was reported at regional level within the Indian states, from 64·8 in Goa to 34·0 in Assam. An even higher level of disparity was reported for China at a 43.5-point difference between the best (Beijing 91.5) and worst performing (Tibet 48.0) subnational location.15 Of note is the fact that even the worst performing region in China scored better than the national average for India, signifying a long road ahead for India towards achieving health for all.

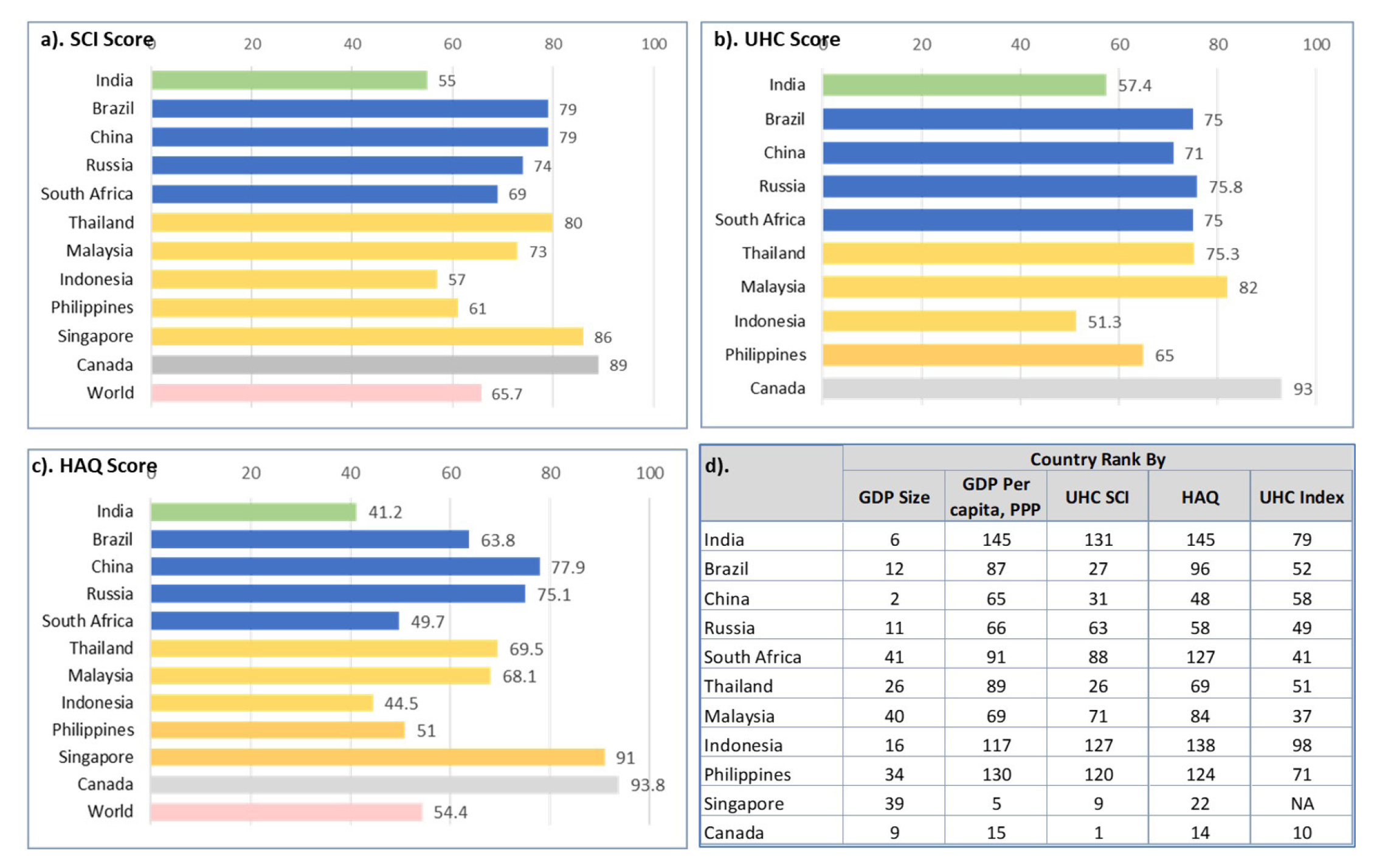

The Service Coverage Index used for measuring UHC performance utilizes indicators belonging to four categories: 1. Reproductive, Maternal, New-born and Child Health (RMNCH), 2. Infectious disease, 3. Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD), and 4. Service capacity and access.2 Sub-indicators such as access to family planning, antenatal care, immunisation for DTP3, and childcare seeking behaviour are used for RMNCH, Tuberculosis (TB) treatment, HIV treatment, insecticide treated nets, and basic sanitation for Infectious disease, Hypertension, fasting glucose level, cervical cancer screening, and tobacco control for NCD and hospital bed density, health worker density, access to essential medicines, and compliance to international health regulations are the indicators used for Service capacity and access [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparison of India with BRICS and ASEAN-5 countries on a) SCI Component Scores b) Availability of Hospital Beds and Physician density per 10,000 population (1 icon = 7 units).

India has been making concerted efforts in improving maternal and neonatal care over years and has launched several programmes for reducing maternal and infant mortality. This shows in its relatively better performance on RMNCH indicator scores. There has been appreciable effort for creating registries and Directly Observed Treatment (DOTS) centres for TB and progress on HIV control, but the country still lags on these parameters as also on basic sanitation, thus impacting infectious disease service component score.2,15 NCD scores are better in terms of service coverage, but the exponentially rising burden of these diseases puts an ever-increasing strain on the healthcare system which is not adequately accessible and needs to be aligned to cater to the lifestyle disease counselling, prevention and treatment.

The area where India lags significantly is Service capacity and Access where it has a score as low as 44 despite an exceptionally high score of 94 in the sub-parameters of having internationally compliant regulations.2,15 In terms of regulations, India has been performing exceedingly well with some well-designed policies to ensure wide access to affordable and quality medicines. These include regularly updated list of essential medicines, with the latest National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) updated in 2022.16 The essential medicines are available free of cost at public hospitals and have a ceiling price announced periodically to control Out-of-Pocket (OOP) cost to patients purchasing from private pharmacies. Similarly, New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules 2019 and Medical Devices Rules 2017 have been published by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization for facilitating transparent and faster approval process of drugs and devices, in line with globally acceptable norms.17 Indian Pharmacopoeia is also regularly updated to keep pace with global quality standards, with the 9th edition released in 2022.18 However, a serious deficit in infrastructure and adequately trained health-workforce is a major concern that continues to undermine efforts to provide healthcare to all in the country, made worse by inequitable distribution of these resource. There were 156101 and 1718 Sub Centres (SCs), 25140 and 5439 Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and 5481 and 470 Community Health Centres (CHCs) in rural and urban India respectively as on 31st March 2021.19 Only 11% of SHC, 16% of PHCs and 16% CHCs meet the Indian Public Health Standards.20 There is gross shortage of specialists and general physicians at all levels of system with 9.6% PHCs without a doctor, 33.4% without a Lab Technician and 23.9% without a pharmacist. At the CHC level, out of the sanctioned posts for specialists, 72.5% are vacant and there is a shortfall of 81.8% specialists as compared to the requirement for the population served.20

India has 7.4 physicians per 10,000 population21 much below the global average of 16.4 and the WHO recommended minimum threshold of 10 per 10,000 population, with the situation further worsened by disparities in distribution where the subnational low is 3.3 physicians per 10,000 population.22 The overall health workforce density has been reported to be between 19.6 to 29 based on census and National Sample Survey Organization data. However, of grave concern is the existence of unqualified workforce in this estimate which is as high as 45-56%, thus reducing the actual qualified physician density to about 4 and total healthcare workers to between 9-16 per 10000 population, which is much below the WHO recommended minimum threshold of 22.8.20–25 Further, 77.4% of all qualified healthcare workers are located in urban areas where only 31% of total population resides25 leaving the rural population with minimal access to qualified healthcare professionals.

Availability of hospital beds is another indicator where India fares poorly compared to global average and other similar economies. In India 5.3 hospital beds are available per 10,000 population which is much below the global average of 29 beds per 10,000 population and is also much below the BRICS and ASEAN-5 countries average7,21 [Figure 2].

Performance on the Financial Protection Dimension of UHC

By definition, the second critical component of UHC is ensuring that families do not suffer undue financial hardship while they access quality healthcare. To monitor financial hardship two type of indicators are used: catastrophic spending on health (SDG indicator 3.8.2) and impoverishing health spending (related to SDG indicator 1.1.1).26 Catastrophic healthcare spending is defined as large household expenditure on health, with large expenditure assumed as those being at 10% and 25% of total household expenditure or income. When such large proportions are required to be spent on health, families deprive themselves of other necessary commodities and may lead a life of deprivation and eventually impoverishment.

India spends only 3% of its GDP on health while the global average is ~10% (2019), of this the general government expenditure on health is ~1.3% of GDP (vs. ~6% global average and between 3-4% of GDP as health expenditure for many comparative ASEAN countries).27–29 The government health expense as a proportion of GDP has been increasing, from 3.4% of total government expenditure in 2015-16 to 4.8% in 2018-19,29 but still remains low vs. other BRICs and ASEAN-5 country governments spending 7-12% of their overall expenditure. While these comparative data are a reflection of lower priority that healthcare currently gets in in India compared with the economies it identifies with, there is increasing acknowledgment of need to correct this aberration as the government of India targets an increase in the public spending on healthcare to 2.5% of GDP by 2025.

As a consequence of low share that healthcare receives in the government budget, a large proportion of the expense, about 55%, needs to be borne as Out-of-Pocket Expense (OOPE) in India, which is among the highest in the world and about thrice the global average of 18%. The most recent National Health Accounts (2018-19) report indicates a downward trend in OOPE, estimated at 48.2% of total healthcare expenditure29 which is a positive sign, but still much above the global average. With ever increasing cost of healthcare and high OOPE, 17.3% population in India ended up spending over 10% of their household consumption or income only on meeting expenses related to healthcare and about 4% spend over one-fourth of their household consumption or income, severely limiting their capacity to lead a dignified life fulfilling their basic needs.7,30 Brazil, despite guaranteeing healthcare as a constitutional right for all its citizen, and China, despite its socialist foundation, are the other two countries in the comparator set that surprisingly perform rather poorly on this indicator. But most ASEAN-5 countries fare much better, especially Malaysia and Thailand [Table 1].

| Incidence of Catastrophic Expenditure (%) | Incidence of Impoverishment due to OOPE (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 10% of household consumption or income | At 25% of household consumption or income | Poverty Line at 2011 PPP $1.90 | Poverty Line at 2011 PPP $3.20 | Relative Poverty Line* | |

| India | 17.3 | 3.9 | 4.16 | 4.44 | 3.23 |

| Brazil | 25.6 | 3.5 | 1.04 | 2.16 | 2.62 |

| China | 19.7 | 5.4 | 1.48 | 3.39 | 4.19 |

| Russia | 4.9 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.01 | 1.79 |

| S. Africa | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.5 |

| Thailand | 2.22 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.62 |

| Malaysia | 0.7 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.44 |

| Indonesia | 2.71 | 0.5 | 0.31 | 0.83 | 0.9 |

| Philippines | 6.31 | 1.4 | 0.48 | 1.35 | 0.96 |

| Singapore | 9.01 | 1.5 | – | – | – |

| Canada | 2.6 | 0.5 | 0.03 | – | 1.24 |

| World | 12.3 | 2.9 | 1.66 | 1.59 | 2.56 |

The high level of OOPE in India makes health cost the single biggest cause of debt, pushing about 3-4% of population31 or 40-50 million people into poverty every year. Globally, 70 million people (1%) were pushed into extreme poverty (below $1.90 per person per day in 2011 purchasing power parity terms) in 2017, while 118 million (2%) were pushed below $3.20 per person per day poverty line and 172 million were pushed into poverty defined in relative terms (below 60% of median daily per capita consumption or income in their country).7,30,32 India contributes a significantly large burden to such impoverishment globally that can be addressed through effective healthcare policies and infrastructure ensuring UHC.

The UHC index has been designed as a geometric average of financial protection and service coverage to provide a comprehensive performance indicator, allowing each dimension to be traded off against each other at a diminishing rate.4 Unlike the earlier described indices of SCI and HAQ, service coverage here neither included health outcomes data nor did it include the upstream influencing parameters such as health policy or health infrastructure. Delivery of preventive healthcare was measured using parameters such as antenatal care, full immunization, breast cancer screening and cervical cancer screening, while treatment access used measures of skilled birth attendance, treatment of acute respiratory infection and diarrhoea, and in-patient admission in previous 12 months. The most recent data available for each country was used for estimating these indicators, which is 2010 for India. Austria with a UHC index score of 95.9 tops the list, followed by France with a score of 95.8. In comparison, UHC score for India is 57.4, with the most significant subduing effect contributed by the near negligible breast cancer and cervical cancer screening rates.

DISCUSSION

Being the second most populous country in the world and home to about 18% of global population, India plays an important role in progress towards achieving the health for all goal of SDG. In addition to the sheer size, Indian healthcare situation is complicated by its diverse regional, social, ethnic, cultural, demographic, economic and political imperatives that must be addressed holistically for effective design and implementation of UHC programs. Major improvement has been seen on various health indicators over the years with several successes and improvement in health outcomes, such as skilled birth attendance increased to 89% in 2019-2021 vs. 44% in 2010 used for estimating UHC index, proportion of pregnant women receiving at least 4 antenatal care visits increased to 59% in 2019-2021 vs. 43.8% considered in UHC index, and rate of full immunization increased from 54% used in this analysis to 77% in 2019-2021.4,33 With these improved indices, one can expect significant lift in the UHC index in the next iteration.

The country needs to further consolidate these gains to catch up with its peer economies on almost all indicators identified by WHO. A comparison of UHC policies and coverage in other BRICS countries vs. India [Table 2] highlights the need for expanding healthcare coverage to match the health outcomes and UHC indicators.

| Population Covered | Coverage Principle | |

|---|---|---|

| India | 35-40% | Fragmented federal and state level initiatives cover parts of population, supplemented by private insurance by some. The recently launched PM-JAY or Ayushman Bharat scheme is the most ambitious of all, with an aim to cover about 40% of the poorest population of the country. Free outpatient and inpatient care are available at public hospitals, but the accessibility, availability, and quality of care at such services are highly limited. Hence, over 75% healthcare service is provided by private sector facilities. |

| Brazil | 100% | “Health is a right of every citizen, and a duty of the State” as per the new constitution of 1988. Unified Health System, SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde) is a unique social project whose principles of universality, comprehensiveness and fairness are established in the Constitution. All healthcare needs are covered including primary care. |

| China | >95% | Cooperative Medical Insurance programs: New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS), Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI) which targets the unemployed, children, students, and the disabled in urban areas, Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) which is an employment-based insurance program. Inpatient care is reimbursed @ 44% in NCMS, 48% in URBMI and 68% in UEBMI; Outpatient care for major and chronic diseases covered by 90-100% countries. |

| Russia | 100% | Based on Semashko model of medical care developed during Soviet Union time. Grants all citizens the right to free medical care- in 1918 marked the first universal coverage in the world Every Russian citizen and resident receives free public healthcare under the Russian healthcare system via Obligatory Medical Insurance (OMI). All citizens have the right to medicines for inpatient care. Some population groups have the right to a 50% discount on medicines for outpatient treatment. |

| South Africa | 85% | National Health Insurance (NHI) is a health financing system that is designed to pool funds to provide access to quality affordable personal health services for all South Africans. NHI is being implemented in phases over a 14-year period that started in 2012. Established through creation of a single fund that buys services on behalf of the entire population. |

The recently announced National Health Protection Mission, 2018, also known as Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) or Ayushman Bharat is seen as a bold step by the Government of India towards achieving this goal. This ambitious initiative has two simultaneous components for strengthening the primary health care infrastructure through establishment of 1,50,000 Health and Wellness Centres for improving the service delivery component and insurance cover for tertiary care providing health protection cover of to the bottom 40% poor and vulnerable families against financial risk arising out of catastrophic health episodes. Currently 119 thousand health and wellness centres have already been operationalized across the country and 193 million beneficiaries have been enrolled in the financial protection scheme as of August 2022, which is about 38% of the target population aimed to be covered. The scheme not only covered the cost for over 39 million hospitalizations for the most disadvantaged section of the society since its launch but also enabled in-patient treatment of 8.3 million covid cases for the covered population.34 The mission is a giant stride forward towards India’s commitment to achieve UHC through the network of primary care centres and financial protection to the poorest section of population and is expected to translate to much-improved SCI, HAQ and UHC indices.

CONCLUSION

India is taking significant strides towards achieving the goal of UHC through the launch and expansion of several National Health Programmes. Pharmacists need to keep abreast of these developments and prepare to play an important role in achievement of this goal as one of the most approachable professionals of the healthcare team. Their contribution may especially be important in preventative care and disease management for NCDs such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, cancer screening, patient counselling for drug adherence, and supporting timely referral to tertiary care centres.

Cite this article

Sharma MG, Popli H. India on the Path to Universal Health Coverage-progress Compared with other Emerging Economies of BRICS and ASEAN-5. J Young Pharm. 2023;15(2):326-33.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations sustainable development goals. Historic New Sustainable Development Agenda Unanimously Adopted by 193 UN Members. [[cited Jul 25 2022]]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2015/09 /historic-new-sustainable-development-agenda-unanimously-adopted-by-193-un- members/

- Hogan DR, Stevens GA, Hosseinpoor AR, Boerma T. Monitoring universal health coverage within the Sustainable Development Goals: Development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e152-68. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff A, Flores G, Hsu J, Smitz MF, Chepynoga K, Buisman LR, et al. Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e169-79. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff A, Neelsen S. A comprehensive assessment of universal health coverage in 111 countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(1):e39-49. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Global multidimensional poverty index 2019: Illuminating inequalities. UN Dev Programme (UNDP) Oxf Pover Hum Dev Initiat (OPHI). 2019:9-10. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SS, Bhasin K, Virmani A. Pandemic, poverty and inequality: Evidence from India [working paper]. International Monetary Fund. 2022 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, The Global Health Observatory. SDG Target 3.8 Achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC). 2022 Available from: https://www.who.int/data/g ho/data/major-themes/universal-health-coverage-major

- World Bank Open Data. 2022 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/

- Unicef. Data: Monitoring the situation of Children and Women. 2017 Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL _DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=IND.MNCH_MMR+CME_MRY0..&startPeriod=2000&endPeriod=2022

- HIV facts and Figures. National Aids Control Organisation, Government of India. 2019 [[cited Jul 20 2022]]. Available from: http://naco.gov.in/hiv-facts-figures

- World Bank feature story. 2014 [[cited Jul 20, 2022]]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/05/29/polio-free-india-biggest-achievements-global-health

A polio-free India is one of the biggest achievements in global health. - Cousins S. India is declared free of maternal and neonatal tetanus. BMJ. 2015;350:h2975 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Levels and Trends in Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation United Nations Levels and Trends in Child Mortality Report 2019. [[cited Jul 20 2022]]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/79371/ file/UN-IGME-child-mortality-report-2020.pdf. UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation

- India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators. Nations within a nation: Variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990-2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2017;390(10111):2437-60. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- GBD. Healthcare access and quality collaborators. Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018. 2016;39:2236-71. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2022 [[cited Dec 22 2022]]. Available from: https://main.mohfw .gov.in/newshighlights-104

- Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. [[cited Dec 22 2022]]. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/open cms/opencms/en/Home/

- Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. [[cited Dec 22 2022]]. Available from: https://www.ipc.gov.in /mandates/indian-pharmacopoeia/indian-pharmacopoeia-2022/8-category-en/ 1018-release-of-indian-pharmacopoeia-ip-2022.html

- Rural health statistics highlights, health management information system. Government of India. [[cited Sep 15 2022]]. Available from: https://hmis.nhp.gov.in/do wnloadfile?filepath=publications/Rural-Health-Statistics/RHS%202020-21.pdf

- Lahariya C. ‘Ayushman Bharat’ Program and Universal Health Coverage in India. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55(6):495-506. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2019, Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21 century. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- A universal truth: No health without a workforce. Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization. [[cited Sep 15 2022]]. Available from: https://www.wh o.int/publications/m/item/hrh_universal_truth

- Karan A, Negandhi H, Nair R, Sharma A, Tiwari R, Zodpey S, et al. Size, composition and distribution of human resource for health in India: New estimates using National Sample Survey and Registry data. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e025979 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Anand S, Fan V. [[cited Sep 15 2022]];The health workforce in India, human resources for health observer series No. 16. World Health Organization. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250369

[PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar] - Rao KD, Shahrawat R, Bhatnagar A. Composition and distribution of the health workforce in India: Estimates based on data from the National Sample Survey. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2016;5(2):133-40. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Tracking universal health coverage. Global monitoring report. 2017 [[cited Aug 30 2022]]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259817/9789241513555-eng.pdf

World Health Organization and World Bank. - Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Government of India. [[cited Aug 12 2022]]. Available from: https://www.cbhidghs.ni c.in/showfile.php?lid=1147

National Health Profile 2019, 14th issue. - WHO global health expenditure database, country profiles. [[cited Jul 12 2022]]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/nha/database/country_profile/Index/en

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2022 [[cited Oct 28 2022]]. Available from: https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/NHA%202018-19_07-09-2022_revised_0.pdf

National health accounts, estimates for India, financial year 2018-19. - Global monitoring report on financial protection in health. 2019 [[cited Aug 12 2022]]. Available from: https://files.aho.afro.who.int/afahobckpcontainer/production/files/ 4_Global_monitoring_report_on_financial_protection_in_health_2019.pdf. World Health Organization and World Bank

- United Nations sustainable development goals. [[cited Jun 12 2022]]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/

- Atim C, Bhushan I, Blecher M, Gandham R, Rajan V, Davén J, et al. Health financing reforms for Universal Health Coverage in five emerging economies. J Glob Health. 2021;11:16005 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India 2019-21. [[updated 2022 Mar, cited 2022 Aug 12]]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR375/FR375.pdf

- National Health Authority Annual Report 2021-22, Government of India. [[updated 2022, Aug 31, cited 2022 Nov 5]]. Available from: https://abdm.gov.in:8081/uploads/ PMJAY_Annual_Report_25_1f47b3cfa5.pdf