ABSTRACT

Background

Antibiotics are crucial for treating infections in older adults, but misuse can lead to drug-resistant bacteria, posing a global health challenge requiring urgent action. This study aimed to analyze the prescribing pattern of antibiotics among hospitalized older adults and identify factors influencing antibiotic use.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study focused on older adults hospitalized at Thumbay University Hospital, Ajman, UAE, for a period of 12 months. Patients with a hospital stay over 24 hr, receiving at least one antibiotic, were included. Data were collected using a standardized tool from electronic medical records and analyzed using classifications like Charlson Comorbidity Index and various WHO classifications, including AWaRe and INRUD prescribing indicators.

Results

The study included 102 patients who received a total of 338 antibiotics. The most frequently prescribed class was systemic antibacterials, specifically cephalosporins and penems (41.25%). Piperacillin-tazobactam was the most used individual agent. High antibiotic prescribing rates related to skin and soft tissue infections (18.63%), pneumonia (18.04%), sepsis (17.75%), urinary tract infection (10.35%), and fracture and injury (8.57%). Patients generally received an average of 3.31 antibiotic agents. Most antibiotics prescribed were broad spectrum (81.95%), with 72.78% falling under the WHO AWaRe “Watch” group, indicating potential for resistance. Most antibiotics were from the national Essential Medicines List (82.24%) and prescribed using generic names (55.02%). The study also identified the total number of medications prescribed during hospital stay was found to correlate with the number of antibiotics prescribed.

Conclusion

The study unveiled a divergence from the WHO antibiotic prescribing guidelines. It recommends conducting large-scale surveillance studies along with instituting institutional and national guidelines to curb antibiotic misuse and overuse in tertiary care hospitals.

INTRODUCTION

Aging is a gradual process that occurs in the human body, associated with a variety of detrimental changes that heighten the likelihood of disease and mortality.1 These changes are especially noticeable in individuals over the age of 65, often referred to as the geriatric population.2 In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the national policy for senior Emiratis sets the cutoff age for geriatric classification at 60 years or older.3 As of 2020, global data suggests that there are 1 billion individuals aged 60 years and above. This figure is anticipated to rise to 1.4 billion by 2030, and by 2050, the global population of older adults is expected to reach 2.1 billion.4

In the UAE, the geriatric demographic stood at 2% in 2015, and is predicted to increase nine-fold by the end of 2050.5 The growth in the older population can be attributed to a steady decline in fertility rates coupled with increased life expectancy.4

Despite advancements in healthcare prolonging life expectancy, the aging population continues to grapple with a multitude of complex health issues.4 Among these health issues is an increased susceptibility to infectious diseases, due to age-related physiological changes in the body. Factors such as immune system decline, changes in skin and mucosal barriers, degeneration of bone and cartilage, and decreased respiratory function contribute to this heightened risk.6 Furthermore, geriatric care facilities often harbor multi-drug-resistant organisms and other nosocomial pathogens, further exacerbating the risk of infections.4 In the UAE, there were 68 recorded cases of infectious diseases for every hundred thousand patients aged 65 years or older in the third quarter of 2018, which saw a 50% increase in the first quarter of 2019.7 Despite the fact that many of these infectious diseases in older adults can be averted through improved personal hygiene, vaccination, and better environmental sanitation, antibiotic drugs remain a key treatment strategy.8 For over 50 years, antibiotics have been instrumental in human medicine, both as preventive measures and therapeutic treatments, greatly benefiting public health. Unfortunately, in recent years, the pervasive usage, misuse, and improper prescribing of these therapies have markedly reduced the effectiveness of antibiotic drugs, resulting in the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria. This poses a significant health concern that is particularly critical in the geriatric population, who often require antibiotic treatment due to their increased susceptibility to infections.9

Antibiotic resistance is a pressing global health concern. Literature indicates a positive correlation between the use of antibiotics and the level of resistance. It suggests that wise and rational use of these drugs can mitigate resistance.10 However, infections caused by resistant organisms is increasing, outpacing the rate of new antibiotic discovery and synthesis. When infections become resistant to first-line treatments, they necessitate more expensive second-line therapies, resulting in prolonged illness and hospital stays, causing increased healthcare costs and burdening families and societies. Antibiotic resistance also hampers public health efforts to control infectious diseases through specific disease control programs that rely on antibiotics for control and prevention.9 The World Health Organization (WHO) 2014 global surveillance report on antibiotic resistance indicates that this issue of antibiotic resistance is no longer a future threat; it is a current global problem, which will hinder our capacity to treat common infections in communities and hospitals. Unless immediate, coordinated action is taken, we risk entering a post-antibiotic era where even common infectious diseases could become untreatable and fatal.11

Hospitals account for over two-thirds of all antibiotic usage, according to the WHO, making them the most commonly prescribed medications in these settings worldwide.10,12 It is essential to understand the prescribing patterns of antibiotics to promote their rational and effective use in hospitals. However, despite numerous studies conducted at the community and outpatient levels across the UAE, there is a noticeable gap in research addressing the inpatient prescribing patterns, particularly within the geriatric population.13,14 The escalating challenge of antibiotic resistance, combined with a slowdown in the development of new antibiotics, intensifies the need to study and streamline antibiotic usage. This urgency underscores the objective of our study, which aims to describe the pattern of antibiotic use among hospitalized older adults and identify associated factors, in order to pinpoint priority areas for future interventions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, study setting, and study period

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted for 12 months at Thumbay University Hospital, Ajman, UAE. As the largest private academic hospital in the Middle East, Thumbay University Hospital provides a wide range of healthcare services to a diverse patient population. This state-of-the-art medical facility, with a 350-bed capacity, advanced technology, and highly skilled medical professionals, is known for its patient-centered healthcare services.

Study population and sampling

All older adults admitted to Thumbay University Hospital from January to December 2021, who met the eligibility criteria, constituted our source population. We used a convenience sampling technique to select patients, and evaluated their electronic medical records to retrieve the necessary data.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study encompassed patients of both genders aged 60 years and older who had been hospitalized for a minimum duration of 24 hr and had been prescribed at least one antibiotic for either treatment or prophylactic purposes during their hospitalization. Conversely, the exclusion criteria comprised patients who were receiving care on an outpatient basis, ensuring that the study focused specifically on the inpatient population within the specified age group.

Study instruments

Through an extensive literature review, a standardized data collection tool was designed to gather and document all pertinent data. This tool encompassed all relevant details, including the patients’ socio-demographic and clinical data, laboratory and diagnostic investigations, and medication profiles. The designed tool was checked for completeness through expert review with an infectious disease specialist. A pilot study was also conducted to test the tool’s reliability in extracting all relevant information. Following the pilot study, necessary corrections were made to the data collection tool, which was then used to retrieve data for the study.

Several other instruments were also utilized in the study for comprehensive data analysis. The documented diagnoses of patients were classified according to the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). To anticipate the mortality risk from comorbid diseases, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was utilized. The WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification was employed to categorize the prescribed antibiotics based on the organ systems they act upon, along with their therapeutic, pharmacologic and chemical properties. Furthermore, the WHO AWaRe Classification was used to distribute antibiotics into AWaRe categories: Access, Watch, and Reserve. Lastly, the prescribing pattern of the healthcare system was assessed using the WHO and International Network for the Rational Use of Drugs (INRUD) prescribing indicators.

Data collection procedure

On a weekly basis, the trained research student reviewed the electronic medical records of patients who met the study’s inclusion-exclusion criteria. Using the data collection tool, the research student extracted relevant patient data from the hospital information system. This included baseline socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and Body Mass Index (BMI), as well as clinical and outcome characteristics like admission diagnosis, presumed infectious diagnosis, previous hospitalization, duration of hospitalization, death, discharge, and laboratory procedures for the diagnosed infection such as culture and susceptibility testing. Additionally, information regarding previous antibiotic therapy within the last 30 days and current antibiotic use, including the type and number of antibiotics administered, dose, dosage form, route of administration, frequency, indication, and duration of administration, etc. were collected.

Data quality management

To maximize the quality of data, the research student was trained on how to fill out the data collection instrument and extract the necessary information. The principal investigator regularly reviewed and supervised the collected data for quality and accuracy. After data collection, the data was cleaned, categorized, compiled, and checked for completeness and accuracy before statistical analysis. Any identified errors were immediately corrected.

Data interpretation and statistical analysis

The collected data was coded and exported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe continuous variables, while categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Chi-square tests were employed to examine the association between the prescribing pattern and explanatory variables (such as age, gender, number of comorbid and infectious conditions, length of stay, previous hospitalization, medication count during hospitalization, and prior 30-day antibiotic use).

Ethical consideration

Prior to commencing the study, approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Gulf Medical University and Thumbay University Hospital (with Institutional Ethical Clearance reference number IRB/COP/STD/30/Dec-2021). The approval letter was subsequently communicated to the hospital administrator before initiating the study. Since this was a retrospective study, written informed consent was waived. The information collected from medical records was strictly used for academic and research purposes. To ensure patient confidentiality, no names or other identifying information of the patients were collected. The data collected was securely stored in electronic format with password protection, further safeguarding patient privacy.

RESULTS

Over the study period, 424 geriatric patients were hospitalized. Of these, 146 were on at least one antibiotic. However, 27 patients were excluded due to being transferred/discharged/died within 24 hr, and 17 were excluded due to readmission with the same medical diagnosis, to avoid data duplication, leaving 102 patients included in the study.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study patients

Of 102 patients in the study, 77 (75.49%) were males and 25 (24.50%) females. The average age was 67.77 years, with more than two-thirds falling under the young-old age group of 60-69 years. Most respondents had a normal BMI (44.11%) and were of 26 different nationalities, predominantly South Asian (34.31%). Most had never smoked (79.41%) or drunk alcohol or had stopped drinking altogether (93.13%) (Table 1).

| Variables | Category | Frequency (N =102) | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60-69 | 75 | 73.52% |

| 70-79 | 16 | 15.68% | |

| >80 | 11 | 10.78% | |

| Mean, SD | 67.77, 7.9177 | ||

| Gender | Male | 77 | 75.49% |

| Female | 25 | 24.50% | |

| BMI | <18.5 | 8 | 7.84% |

| 18.5-24.9 | 45 | 44.11% | |

| 25-29.9 | 31 | 30.39% | |

| >30 | 18 | 17.64% | |

| Mean, SD | 25.62, 6.1355 | ||

| Nationality | South Asia | 35 | 34.31% |

| Southeast Asia | 8 | 7.84% | |

| Middle East | 33 | 32.35% | |

| Africa | 23 | 22.54% | |

| North America | 2 | 1.96% | |

| Europe | 1 | 0.98% | |

| Smoking behaviour | Current smokers | 18 | 17.64% |

| Ex-smokers | 3 | 2.94% | |

| Never smokers | 81 | 79.41% | |

| Drinking behaviour | Current drinkers | 7 | 6.86% |

| Abstainers | 95 | 93.13% | |

A total of 40 patients (39.21%) had no prior illnesses. Among those with past conditions, 74.19% had 1-4 illnesses, and 25.80% had five or more. Post-admission, patients with five or more illnesses increased to 50.98%. Around 60.00% and 36.25% were diagnosed with one or two infectious diseases after admission. Concerning the Charlson comorbidity index, 33.33% had a low 12-month mortality rate, while most had an 81-100% 10-year survival rate (31.37%). Around 94.11% stayed for 11 days or more days (average 30.37 days). About 43.13% had a history of hospitalization in the previous 30 days. Only 18.62% required intensive care during hospitalization. Of all, 68.62% recovered, while 2.94% discharged against medical advice, 5.88% died, and 22.54% were transferred (Table 2). Analysis of patients’ diagnosis revealed the most prevalent were circulatory (18.16%) and endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic (13.57%) diseases. Genitourinary (9.56%) and respiratory (8.60%) diseases were third and fourth, followed by nervous system diseases (7.07%) (Table 3). A detailed ICD-10 diagnostic table is in supplementary material (Table S1).

| Variables | Category | Frequency (N =102) | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of past medical history. | Yes | 62 | 60.78% |

| No | 40 | 39.21% | |

| Number of past diseases (N=62). | 1-4 | 46 | 74.19% |

| >5 | 16 | 25.80% | |

| Mean, SD | 2.06, 2.4746 | ||

| Number of admission diagnosis. | 1-4 | 50 | 49.01% |

| >5 | 52 | 50.98% | |

| Mean, SD | 5.08, 3.0575 | ||

| Number of healthcare-associated infections diagnosed following hospital admission (N=80). | 1 | 48 | 60.00% |

| 2 | 29 | 36.25% | |

| 3 | 3 | 3.75% | |

| Mean, SD | 1.12, 0.7793 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity scoring system based on newly diagnosed medical conditions. | 12-month mortality rate Low | 34 | 33.33% |

| Medium | 38 | 37.25% | |

| High | 21 | 20.58% | |

| Very high | 9 | 8.82% | |

| 10-year survival rate | |||

| 0-20 | 25 | 24.50% | |

| 21-40 | 12 | 11.76% | |

| 41-60 | 14 | 13.72% | |

| 61-80 | 19 | 18.62% | |

| 81-100 | 32 | 31.37% | |

| Mean, SD | 53.23, 36.9571 | ||

| Previous hospitalization in last 30 days. | Yes | 44 | 43.13% |

| No | 58 | 56.86% | |

| Length of hospital stay. | <5 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 6-10 | 6 | 5.88% | |

| >11 | 96 | 94.11% | |

| Mean, SD | 30.37, 19.3134 | ||

| Required intensive care admission during hospitalization. | Yes | 19 | 18.62% |

| No | 83 | 81.37% | |

| Outcome of treatment. | Recovered | 70 | 68.62% |

| Dead | 6 | 5.88% | |

| Refered | 23 | 22.54% | |

| Discharged against medical advice | 3 | 2.94% | |

| Variables | Frequency (N=523) | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Certain infectious and parasitic diseases (A00-B99). | 29 | 5.54% |

| Neoplasms (C00-D49). | 3 | 0.57% |

| Diseases of the blood and blood forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism (D50-D89). | 7 | 1.33% |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (E00-E89). | 71 | 13.57% |

| Mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders (F01-F99). | 18 | 3.44% |

| Diseases of the nervous system (G00-G99). | 37 | 7.07% |

| Diseases of the eye and adnexa (H00-H59). | 6 | 1.14% |

| Diseases of the ear and mastoid process (H60-H95). | 2 | 0.38% |

| Diseases of circulatory system (I00-I99). | 95 | 18.16% |

| Diseases of respiratory system (J00-J99). | 45 | 8.60% |

| Diseases of digestive system (K00-K95). | 23 | 4.39% |

| Diseases of skin and subcutaneous tissue (L00-L99). | 36 | 6.88% |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99). | 17 | 3.25% |

| Diseases of genitourinary system (N00-N99). | 50 | 9.56% |

| Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00-R99). | 25 | 4.78% |

| Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes (S00-T88). | 34 | 6.50% |

| Codes for special purposes (U00-U85). | 9 | 1.72% |

| External causes of morbidity (V00-Y99). | 1 | 0.19% |

| Factors influencing health status and contact with health services (Z00-Z99). | 15 | 2.86% |

Prior to hospitalization, 60.78% of patients were on medications, with 75.80% using fewer than five chronic medicines. Approximately 22.58% had low-level polypharmacy (5-9 chronic medications), and only one patient had high-level polypharmacy (10 or more medications). In the hospital, 81.37% had high-level polypharmacy, while 18.62% had low-level. Among the patients, 88.23% had no recent antibiotic drug use, while 12 (11.76%) did. These 12 patients were prescribed 24 antibiotics in total, with most (50.00%) receiving two antibiotics (Table 4).

| Variables | Category | Frequency (N =102) | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past medication history. | Yes | 62 | 60.78% |

| No | 40 | 39.21% | |

| Number of past medications (N=62). | 1-4 | 47 | 75.80% |

| 5-9 | 14 | 22.58% | |

| > 10 | 1 | 1.61% | |

| Mean, SD | 2.30, 2.5438 | ||

| Number of medications prescribed during hospital stay. | 1-4 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 5-9 | 19 | 18.62% | |

| > 10 | 83 | 81.37% | |

| Mean, SD | 13.10, 3.7792 | ||

| Antibiotic use history in last 30 days. | Yes | 12 | 11.76% |

| No | 90 | 88.23% | |

| Number of antibiotics prescribed in last 30 days (N=12). | 1 | 3 | 25.00% |

| 2 | 6 | 50.00% | |

| >3 | 3 | 25.00% | |

| Mean, SD | 0.11, 0.99 | ||

Prescribing pattern of antibiotics among study patients

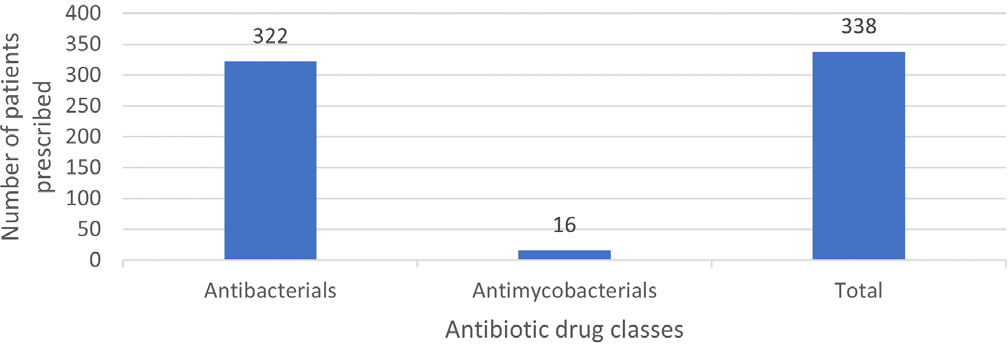

The study participants were prescribed a total of 338 antibiotics, of which 322 (95.26%) were antibacterial agents, highlighting a much higher usage rate compared to the 16 (4.73%) antimycobacterial drugs (Figure 1). Of 338 antibiotics investigated, systemic antibacterials (94.67%) were most prescribed. Systemic antimycobacterials (4.73%) and topical antibacterials (0.59%) were rarely used. Within systemic antibacterials, cephalosporins and penems (41.25%) and penicillins (25.31%) were common. When considering individual agents, piperacillin-tazobactam was most frequently used (N=57) (Table 5). Disease wise antibiotic prescribing is detailed in supplementary material (Table S2). Antibiotics were mainly prescribed for skin and soft tissue infections (18.63%), pneumonia (18.04%), sepsis (17.75%), urinary tract infection (10.35%), and fracture and injury (8.57%). Penicillins were frequently used for skin and soft tissue infection (17.46%), pneumonia (24.59%) and sepsis (28.33%), except urinary tract infections (20.00%) and fractures (20.68%), where cephalosporins were preferred.

| Antibiotic class | Type of individual antibiotic agent | ATC code | Number of cases | Total (%) (N=338) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatologicals | ||||

| Antibiotics and chemotherapeutics for dermatological use | 2 (0.59) | |||

| Antibiotics for topical use | 2 (100.0) | |||

| Other antibiotics for topical use | Mupirocin | D06AX09 | 2 | 2 (100.0) |

| Antiinfectives for systemic use | ||||

| Antibacterials for systemic use | 320 (94.67) | |||

| Tetracyclines | 9 (2.81) | |||

| Tetracyclines | Doxycycline | J01AA02 | 4 | 9 (100.0) |

| Tigecycline | J01AA12 | 5 | ||

| Beta-lactam antibacterials, Penicillins | 81 (25.31) | |||

| Penicillins with extended spectrum. | Ampicillin | J01CA01 | 1 | 1 (1.23) |

| Beta-lactamase resistant penicillins. | Flucloxacillin | J01CF05 | 3 | 3 (3.70) |

| Combinations of penicillins, including beta-lactamase inhibitors. | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | J01CR02 | 20 | 77 (95.06) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | J01CR05 | 57 | ||

| Other beta-lactam antibacterials | 132 (41.25) | |||

| Second-generation cephalosporins. | Cefuroxime | J01DC02 | 25 | 25 (18.93) |

| Third-generation cephalosporins. | Ceftriaxone | J01DD04 | 51 | 55 (41.66) |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | J01DD52 | 4 | ||

| Fourth-generation cephalosporins. | Cefepime | J01DE01 | 3 | 3 (2.27) |

| Carbapenems | Meropenem | J01DH02 | 37 | 46 (34.84) |

| Ertapenem | J01DH03 | 9 | ||

| Other cephalosporins and penems. | Ceftolozane-tazobactam | J01DI54 | 3 | 3 (2.27) |

| Sulfonamides and trimethoprim | 2 (0.62) | |||

| Combinations of sulfonamides and trimethoprim, including derivatives. | Sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim | J01EE01 | 2 | 2 (100.0) |

| Macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins | 10 (3.12) | |||

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | J01FA01 | 1 | 6 (60.00) |

| Azithromycin | J01FA10 | 5 | ||

| Lincosamides | Clindamycin | J01FF01 | 4 | 4 (40.00) |

| Aminoglycoside antibacterials | 4 (1.25) | |||

| Other aminoglycosides | Gentamicin | J01GB03 | 2 | 4 (100.0) |

| Amikacin | J01GB06 | 2 | ||

| Quinolone antibacterials | 35 (10.93) | |||

| Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin | J01MA02 | 8 | 35 (100.0) |

| Levofloxacin | J01MA12 | 26 | ||

| Moxifloxacin | J01MA14 | 1 | ||

| Other antibacterials | 47 (14.68) | |||

| Glycopeptide antibacterials. | Vancomycin | J01XA01 | 13 | 19 (40.42) |

| Teicoplanin | J01XA02 | 6 | ||

| Polymyxins | Colistimethate | J01XB01 | 6 | 6 (12.76) |

| Imidazole derivatives | Metronidazole | J01XD01 | 11 | 11 (23.40) |

| Nitrofuran derivatives | Nitrofurantoin | J01XE01 | 1 | 1 (2.12) |

| Other antibacterials | Linezolid | J01XX08 | 10 | 10 (21.27) |

| Antimycobacterials | 16 (4.73) | |||

| Drugs for treatment of tuberculosis | 16 (100.0) | |||

| Antibiotics | Rifampicin | J04AB02 | 4 | 4 (25.00) |

| Hydrazides | Isoniazid | J04AC01 | 4 | 4 (25.00) |

| Other drugs for treatment of tuberculosis. | Pyrazinamide | J04AK01 | 4 | 8 (50.00) |

| Ethambutol | J04AK02 | 4 | ||

Figure 1:

Spectrum of antibiotic usage among patients during hospital stay.

Most patients were given three or more antibiotics (61.76%), averaging 3.31 per patient. According to 2021 AWaRe classification, 72.78% of the antibiotics used fell under the ‘Watch’ group, while ‘Reserve’ group antibiotics constituted 8.28%. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were most ordered (81.95%), with 25.44% given as a combination therapy and 74.55% as a single antibiotic. The parenteral route was used in 86.09% cases. Most antibiotics were given thrice daily (31.95%), with an average treatment duration of 8.58 days. Cultures, primarily from urine, were available for 86.27% of patients. Klebsiella pneumoniae (15.15%), Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (12.12%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11.11%) were the most common organisms isolated. Culture sensitivity was obtained before antibiotic initiation in 45.09% of patients. (Table 6). Around 82.24% of the antibiotics were prescribed from the national essential medicines list (EML), and 55.02% using generic names. Antibiotics were empirically prescribed in 57.84% of cases, and 65.68% had targeted therapy based on culture results. Around 20.58% received prophylactic therapy, and 13.72% for unknown reasons (Table 7).

| Variables | Category | Frequency (N =102) | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of antibiotics at a time. | 1 | 13 | 12.74% |

| 2 | 26 | 25.49% | |

| >3 | 63 | 61.76% | |

| Mean, SD | 3.31, 1.7404 | ||

| AWaRe classification (N =338). | Access | 50 | 14.79% |

| Watch | 246 | 72.78% | |

| Reserve | 28 | 8.28% | |

| Not classified | 14 | 4.14% | |

| Spectrum of activity (N=338). | Broad | 277 | 81.95% |

| Narrow | 61 | 18.04% | |

| Type of antibiotic treatment (N=338). | Monotherapy | 252 | 74.55% |

| Combination therapy | 86 | 25.44% | |

| Route of administration (N=338). | Oral | 45 | 13.31% |

| Injectable | 291 | 86.09% | |

| Topicals | 2 | 0.59% | |

| Frequency of administration (N=338). | Once daily | 63 | 18.63% |

| Two times daily | 104 | 30.76% | |

| Three times daily | 108 | 31.95% | |

| Four times daily | 63 | 18.63% | |

| Antibiotic days (N =338). | <3 days | 38 | 11.24% |

| 4-5 days | 63 | 18.63% | |

| 6-7 days | 109 | 32.24% | |

| >7 days | 128 | 37.86% | |

| Mean, SD | 8.58, 4.5134 | ||

| Culture available. | Yes | 88 | 86.27% |

| No | 14 | 13.72% | |

| Specimen for culture (N=203). | Blood | 64 | 31.52% |

| Urine | 68 | 33.49% | |

| Stool | 10 | 4.92% | |

| Sputum | 35 | 17.24% | |

| Wound | 14 | 6.89% | |

| Others | 12 | 5.91% | |

| Culture results (N=203). | Positive | 99 | 48.76% |

| Negative | 104 | 51.23% | |

| Organisms commonly isolated (N=99). | Acinetobacter baumannii | 3 | 3.03% |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | 2 | 2.02% | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 | 1.01% | |

| Candida albicans | 11 | 11.11% | |

| Citrobacter koseri | 1 | 1.01% | |

| Cutibacterium acnes | 2 | 2.02% | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 4 | 4.04% | |

| Escherichia coli | 9 | 9.09% | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 | 1.01% | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 15 | 15.15% | |

| Methicillin-resistant staphyloco ccus aureus | 12 | 12.12% | |

| Proteus mirabilis | 3 | 3.03% | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 11 | 11.11% | |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 | 1.01% | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3 | 3.03% | |

| Staphylococcus capitis | 1 | 1.01% | |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 3 | 3.03% | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 8 | 8.08% | |

| Mixed microbes | 8 | 8.08% | |

| Culture sensitivity test available prior to initiating antibiotics. | Yes | 46 | 45.09% |

| No | 56 | 54.90% | |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Average number of drugs prescribed per patient. | 13.11, 3.7792 | |

| Average number of antibiotics prescribed per patient. | 3.31, 1.7404 | |

| Percentage of antibiotics prescribed from national EML. | 278 | 82.24% |

| Percentage of antibiotics prescribed by generic name. | 186 | 55.02% |

| Percentage of antibiotics prescribed in injection form. | 291 | 86.09% |

| Percentage of antibiotics prescribed in oral form. | 45 | 13.31% |

| Average duration of days antibiotics was prescribed in hospital stay. | 8.58, 4.5134 | |

| Percentage of patients who received antibiotics for therapeutic purposes. | 67 | 65.68% |

| Percentage of patients who received antibiotics for prophylaxis. | 21 | 20.58% |

| Percentage of patients who received antibiotics for unknown purpose. | 14 | 13.72% |

| Percentage of patients who received antibiotics for empiric therapy. | 59 | 57.84% |

Factors associated with prescribing antibiotics among study patients

Under chi-square test, the number of medications prescribed during hospital stay (p=0.0026) was associated with the number of antibiotics prescribed. Patients who were prescribed 10 or more medications overall during their hospital stay were significantly more likely to have been prescribed more than two antibiotics during their stay, as compared to those who were prescribed fewer medications (Table 8).

| Variables | Category | Number | Chi-square P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥2 antibiotics | >2 antibiotics | |||

| Age | 60-69 | 27 | 48 | 0.7380 |

| 70-79 | 7 | 9 | ||

| >80 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Gender | Male | 29 | 48 | 0.8344 |

| Female | 10 | 15 | ||

| Presence of comorbid conditions. | Yes | 23 | 39 | 0.7683 |

| No | 16 | 24 | ||

| Number of admission diagnosis. | 1-4 | 21 | 29 | 0.4429 |

| >5 | 18 | 34 | ||

| Number of healthcare-associated infections diagnosed following hospital admission. | <1 | 31 | 39 | 0.0629 |

| >2 | 8 | 24 | ||

| Length of hospital stay. | <10 | 3 | 3 | 0.5410 |

| >11 | 36 | 60 | ||

| Previous hospitalization in last 30 days. | Yes | 16 | 28 | 0.7347 |

| No | 23 | 35 | ||

| Number of medications prescribed during hospital stay. | <9 | 13 | 6 | 0.0026* |

| > 10 | 26 | 57 | ||

| Antibiotic use history in last 30 days. | Yes | 4 | 8 | 0.7098 |

| No | 35 | 55 | ||

DISCUSSION

In this study, all older patients were prescribed atleast one antibiotic, as we included only those patients who were on antibiotics. The most frequently prescribed antibiotic classes were cephalosporins and penems (41.25%), followed by penicillins (25.31%). This corroborates earlier studies which found cephalosporins to be the preferred choice, due to their broad-spectrum activity, less frequent dosing, and better safety profile.12,15,16 However, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Alanazi et al. found penicillins to be the most prescribed class.17 Comparable findings were reported by previous local studies done by Mohajer et al.18 and Oqal et al.19 Considering individual agents, piperacillin/ tazobactam was most used, followed by ceftriaxone. These results were generalizable to another retrospective cross-sectional study conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Oman, which also observed piperacillin/tazobactam to be the most commonly prescribed antibiotic agent.20 Our results also echo the ARMed study, which demonstrated that broad-spectrum penicillin, along with first-generation cephalosporin, accounted for the bulk of antibiotics prescribed, constituting at least one-third of the total usage in 15 of 25 hospitals in the Mediterranean region.21 Conversely, ceftriaxone was observed to be the most prescribed antibiotic in several studies conducted in developing nations.10,12,22

Our study found that only 14.79% of antibiotics used were from the ‘Access’ group, which was significantly lower compared to the standard set by the WHO AWaRe Classification, which recommends at least 60% of institutional antibiotic consumption should be from this group.23 This finding was consistent with a global survey demonstrating varied regional use of ‘Access’ antibiotics, ranging from 28.4% in West and Central Asia to 57.7% in Oceania,24 with an average of 34.5% in four developing countries.25 Furthermore, we observed an overuse of ‘Watch’ group antibiotics, with 72.78% of the prescribed antibiotics falling into this category. This observation was much higher than the figures reported by Dechasa et al., who showed that nearly 66% of antibiotics used were from the ‘Watch’ group of antibiotics.12 Similarly, a survey done in West and Central Asia24 and in four low- and middle-income countries25 reported a ‘Watch’ group antibiotic usage count of 66.1% and 64.4% respectively. There is substantial evidence that adhering to a shortlist of essential medicines in any healthcare environment can enhance the pattern of drug utilization, thereby improving patient care.26 Although the WHO recommends that all prescribed antibiotics should be on the national EML, only 82.24% in our study were, echoing deviations seen in studies from countries like Lesotho (79.0%),27 India (84.8%),28 and Pakistan (98.8%).29 Conversely, studies from Ethiopia10 and Eritrea30 exhibited complete adherence, with 100% of prescribed antibiotics coming from the national EML.

Our study found that only 55.02% of antibiotics were prescribed by their generic names, despite a 100% target. The WHO indicators suggest that prescribing antibiotics by their generic names is a significant marker of the adoption of low-cost antibiotics, given it prevents confusion from multiple names for the same product, thereby minimizing the risk of drug replication. This practice should be fully adopted in institutional settings to prevent dispensing errors and redundant treatments.16 Our finding was also substantiated in studies by Ahmed et al.31 (49.3%) and Mudenda et al.32 (56.1%), however, falls significantly short compared to studies from Cameroon (98.36%),9 Ethiopia (97.6%),22 Eritrea (97%),30 and India (98.0%).33 Furthermore, 81.95% of the antibiotics in our study were prescribed as broad spectrum, which is also evident from earlier studies.22,29,34

The study revealed an average of 3.31 antibiotics prescribed per patient, significantly higher than the WHO’s recommended 1.6-1.8, hinting at potential overuse of antibiotics. Our finding exceeded the average antibiotic count reported by Patel et al.,28 Amaha et al.,30 and Gutema et al.34 While efforts should be made to keep the prescription count as low as possible, a higher number may be justified in hospital settings where clinical cases are complicated. The literature indicates a correlation between an increased antibiotic count and the inappropriateness of prescription practices, with the understanding that the higher the number of antibiotics per patient, the more inappropriate the prescription practice becomes. This escalation may also lead to polypharmacy, raising the risk of complications from drug-drug interactions and adverse reactions.10 Parenteral administration was the primary delivery route in this study, accounting for 86.09% of cases, far exceeding the WHO’s 13.4% to 24.1% reference range.35 This trend could be attributed to the late hospital presentation of critically ill patients, as parenteral administration provides rapid symptomatic benefits and is often reserved for such patients. The results of our study align to the study by Demoz et al.22 (84.8%), Amaha et al.30 (81.4%%), and Gutema et al.34 (82.4%), who noticed frequent prescription of parenteral antibiotics. However, it is important to note that overprescription of parenteral antibiotics can burden patients financially and is considered inappropriate antibiotic use, emphasizing the need for de-escalation of prescriptions based on strict necessity.29

Literature states that culture and sensitivity tests should be performed prior to antibiotic prescription, in order to aide prescribers in selecting curative antibiotics. Empirically ordered antibiotics tend to be less appropriate than those prescribed based on culture and susceptibility report data.36 Despite this recommendation, 57.84% of patients received empirical antibiotics without identification of the causative micro-organism. Approximately, 65.68% received targeted therapy based on culture results, 20.58% received antibiotic prophylactic therapy, and for 13.72%, the reasons for antibiotic usage remained unclear. This differs from the findings of Gandham et al.,26 where a higher percentage of study population received antibiotics empirically (44.80%) followed by curatively (34.70%), and prophylactically (20.40%). Studies by Alemkere et al.,15 Ayele et al.,37 and Sileshi et al.,38 also found a predominance of empiric therapy. Another finding in this study showed that antibiotics were prescribed for an average duration of 8.58 days, longer than averages observed in Ethiopia10 (6.4 days) and Eritrea30 (6.36 days). Given the lack of consensus on the ideal duration of therapy for most infectious diseases, it is advisable to treat patients for a minimum of 7-10 days.33 Prescribing antibiotics for durations either shorter or longer than necessary in the hospital setting requires careful examination and can be managed by implementing institutional guidelines. Shorter courses of treatment may contribute to the emergence of resistant micro-organisms, while prolonged exposure raises the risk of adverse drug reactions, antibiotic resistance, and unnecessary expenditure on antibiotics.39

In terms of organisms, Klebsiella pneumoniae (15.15%), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (12.12%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11.11%) were commonly isolated from the study sample specimens. However, in the study conducted by Aly et al., which examined the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates from various Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) countries, Escherichia coli was the most prevalent microorganism, followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Acinetobacter.21 Using chi-square analysis, we observed a significant association between the total number of medications prescribed during hospital stay and the number of antibiotics prescribed (p=0.0026). On the contrary, Abdalla et al.16 and Bansal et al.40 identified a significant link between prescribing pattern and hospital stay duration. Abdalla et al. also reported a statistically significant association between number of antibiotics prescribed and type of medical diagnosis.16

Limitations of the Study

The study’s limitations include its single hospital setting, affecting the generalizability of results due to potential variation in patient characteristics, prescribing patterns, and microbiology resistance patterns across different hospitals. The data collection relied solely on electronic medical records, potentially missing insights from direct interaction with prescribers or patients. The study’s retrospective design might have overlooked certain medication details. Lastly, the relatively small sample size could affect the statistical power and generalizability of the findings.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study focuses on the antibiotic prescribing pattern among older adults hospitalized at Thumbay University Hospital in Ajman, UAE. The findings reveal that the antibiotic prescribing pattern deviated from the recommended WHO standards. Addressing this issue necessitates the implementation of ongoing interventions, conducting regular audits at all levels of healthcare, and developing hospital guidelines and policies that promote better antibiotic utilization. These measures are vital for proper, responsible antibiotic prescribing practices, not just locally but on a larger scale.

| ICD code | ICD chapter title | Disease category | Number of cases | Total (%) (N =523) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A00-B99 | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases. | Infectious gastroenteritis and colitis, unspecified. | 2 | 29 (5.54) |

| Respiratory tuberculosis, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Other tuberculosis of specified organs. | 1 | |||

| Acute military tuberculosis of multiple sites. | 1 | |||

| Sepsis, unspecified organism. | 19 | |||

| Other specified viral infections of central nervous system. | 1 | |||

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease. | 2 | |||

| Staphylococcal aureus as the cause of diseases classified elsewhere, unspecified site. | 1 | |||

| C00-D49 | Neoplasms | Multiple myeloma, without mention of complete remission. | 1 | 3 (0.57) |

| Neoplasm of uncertain behavior of brain, supratentorial. | 1 | |||

| Myelodysplastic syndrome, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| D50-D89 | Diseases of the blood and blood forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism. | Iron deficiency anemia, unspecified. | 4 | 7 (1.33) |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency anemia, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Pancytopenia, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| E00-E89 | Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases. | Subclinical iodine-deficiency hypothyroidism. | 1 | 71 (13.57) |

| Hypothyroidism, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Nontoxic multinodular goiter. | 1 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with ketoacidosis without coma. | 1 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic nephropathy. | 3 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic neuropathy, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic peripheral angiopathy without gangrene. | 9 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with foot ulcer. | 4 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with other specified complications. | 1 | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications. | 22 | |||

| Drug-induced hypoglycemia without coma. | 1 | |||

| Vitamin D deficiency, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Morbid (severe) obesity due to excess calories. | 1 | |||

| Hyperlipidemia, unspecified. | 17 | |||

| Hypo-osmolality and hyponatremia | 6 | |||

| Acidosis, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| F01-F99 | Mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders. | Unspecified dementia without behavioral disturbance. | 7 | 18 (3.44) |

| Delirium due to known physiological condition. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified delirium. | 1 | |||

| Psychotic disorder with delusions due to known physiological condition. | 1 | |||

| Alcohol dependence with withdrawal, delirium. | 2 | |||

| Other psychoactive substance use, unspecified with psychoactive substance-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Depression, unspecified. | 3 | |||

| Unspecified intellectual disability. | 1 | |||

| G00-G99 | Diseases of the nervous system. | Bacterial meningoencephalitis and meningomyelitis, not elsewhere classified. | 1 | 37 (7.07) |

| Encephalitis and encephalomyelitis, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. | 1 | |||

| Parkinson’s disease. | 4 | |||

| Striatonigral degeneration. | 1 | |||

| Essential tremor. | 1 | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease, unspecified. | 5 | |||

| Epilepsy, unspecified, not intractable, without status epilepticus. | 11 | |||

| Migraine, unspecified, not intractable, without status migrainosus. | 1 | |||

| REM sleep behavior disorder. | 1 | |||

| Hemiplegia, unspecified affecting unspecified site. | 5 | |||

| Quadriplegia, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Hydrocephalus, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Anoxic brain damage, not elsewhere classified. | 1 | |||

| Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. | 1 | |||

| H00-H59 | Diseases of the eye and adnexa. | Unspecified age-related cataract | 2 | 6 (1.14) |

| Exudative age-related macular degeneration, bilateral. | 1 | |||

| Peripheral retinal degeneration, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified glaucoma. | 1 | |||

| Subjective visual disturbances. | 1 | |||

| H60-H95 | Diseases of the ear and mastoid process. | Diffuse otitis externa, left ear. | 1 | 2 (0.38) |

| Unspecified hearing loss, bilateral. | 1 | |||

| I00-I99 | Diseases of circulatory system | Essential (primary) hypertension. | 38 | 95 (18.16) |

| Hypertensive emergency. | 1 | |||

| Chronic ischemic heart disease, unspecified. | 11 | |||

| Pulmonary embolism with acute corpulmonale. | 1 | |||

| Nonrheumatic mitral valve disorder, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Nonrheumatic aortic (valve) stenosis | 1 | |||

| Cardiomyopathy, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Atrioventricular block, complete. | 1 | |||

| Bifascicular block. | 1 | |||

| Cardiac arrest, cause unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified atrial fibrillation. | 6 | |||

| Diastolic (congestive) heart failure. | 1 | |||

| Heart failure, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage, unspecified. | 8 | |||

| Cerebral infarction due to thrombosis of precerebral arteries. | 6 | |||

| Cerebral infarction, unspecified. | 4 | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease, unspecified. | 3 | |||

| Peripheral vascular disease, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Embolism and thrombosis of thoracic aorta. | 1 | |||

| Chronic embolism and thrombosis of unspecified deep veins of lower extremity, bilateral. | 1 | |||

| Varicose veins of lower extremities, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Gangrene, not elsewhere classified. | 2 | |||

| J00-J99 | Diseases of respiratory system. | Pneumonia, unspecified organism. | 26 | 45 (8.60) |

| Unspecified acute lower respiratory infection. | 2 | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified asthma, uncomplicated. | 3 | |||

| Pneumonitis due to inhalation of food and vomit. | 5 | |||

| Acute pulmonary edema. | 2 | |||

| Pulmonary fibrosis, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Interstitial pulmonary disease, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Pleural effusion, unspecified. | 4 | |||

| K00-K95 | Diseases of digestive system. | Gastro-esophageal reflux disease without esophagitis. | 1 | 23 (4.39) |

| Gastritis, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Acute appendicitis with generalized peritonitis. | 1 | |||

| Other and unspecified ventral hernia without obstruction or gangrene. | 1 | |||

| Acute (reversible) ischemia of large intestine. | 1 | |||

| Diverticulitis of large intestine without perforation or abscess without bleeding. | 1 | |||

| Diverticulitis of large intestine with perforation and abscess. | 1 | |||

| Functional diarrhoea. | 1 | |||

| Constipation, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Haemorrhage of anus and rectum | 1 | |||

| Hemoperitoneum. | 1 | |||

| Other and unspecified cirrhosis of liver. | 2 | |||

| Abscess of liver. | 1 | |||

| Fatty (change of) liver, not elsewhere classified. | 1 | |||

| Calculus of gall bladder without cholecystitis, without obstruction. | 1 | |||

| Acute cholecystitis. | 1 | |||

| Acute pancreatitis with infected necrosis, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Acute pancreatitis, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Alcohol induced acute pancreatitis without necrosis or infection. | 1 | |||

| Gastrointestinal haemorrhage, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| L00-L99 | Diseases of skin and subcutaneous tissue. | Cutaneous abscess of neck. | 1 | 36 (6.88) |

| Cutaneous abscess of unspecified hand. | 1 | |||

| Cutaneous abscess of foot. | 2 | |||

| Cellulitis, unspecified. | 6 | |||

| Local infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, unspecified. | 4 | |||

| Stevens Johnson syndrome. | 1 | |||

| Rosacea, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Hidradenitis suppurativa. | 1 | |||

| Decubitus (pressure) ulcer of unspecified site, unspecified stage. | 10 | |||

| Granulomatous disorder of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Non-pressure chronic ulcer of unspecified part of unspecified lower leg, with unspecified severity. | 8 | |||

| M00-M99 | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue. | Direct infection of elbow in infectious. and parasitic diseases classified elsewhere. | 1 | 17 (3.25) |

| Osteoarthritis of knee, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Foot drop, unspecified foot. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified acquired deformity of hand, right hand, unspecified site. | 1 | |||

| Pain in unspecified elbow. | 1 | |||

| Systemic involvement of connective tissue, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Other intervertebral disc displacement, lumbar region. | 1 | |||

| Dorsalgia, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Contracture of muscle, unspecified | 2 | |||

| Other muscle spasm. | 1 | |||

| Adhesive capsulitis of shoulder. | 1 | |||

| Pain in unspecified ankle and joints of unspecified foot. | 2 | |||

| Age-related osteoporosis without current pathological fracture, unspecified site. | 2 | |||

| N00-N99 | Diseases of genitourinary system. | Acute kidney failure, unspecified. | 4 | 50 (9.56) |

| Chronic kidney disease, unspecified | 15 | |||

| Calculus of kidney. | 1 | |||

| Acute cystitis without hematuria. | 3 | |||

| Neuromuscular dysfunction of bladder, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Rupture of bladder, nontraumatic. | 1 | |||

| Urinary tract infection, site not specified. | 20 | |||

| Urinary incontinence, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia without lower urinary tract symptoms. | 3 | |||

| R00-R99 | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified. | Cough, unspecified. | 1 | 25 (4.78) |

| Hypoxemia. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified abdominal pain. | 1 | |||

| Vomiting without nausea. | 1 | |||

| Dysphagia, pharyngeal phase. | 2 | |||

| Left upper quadrant abdominal swelling, mass and lump. | 1 | |||

| Localized swelling, mass and lump, lower limb, bilateral. | 1 | |||

| Ataxic gait. | 1 | |||

| Anuria and oliguria. | 1 | |||

| Other amnesia. | 1 | |||

| Disorientation, unspecified. | 1 | |||

| Strange and inexplicable behavior. | 1 | |||

| Aphasia | 1 | |||

| Fever, unspecified | 2 | |||

| Weakness | 1 | |||

| Syncope and collapse. | 1 | |||

| Post traumatic seizures. | 2 | |||

| Shock, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Other symptoms and signs concerning food and fluid intake. | 1 | |||

| Cachexia. | 1 | |||

| Abnormality of albumin. | 1 | |||

| S00-T88 | Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes. | Superficial injury of unspecified body region. | 1 | 34 (6.50) |

| Traumatic subdural hemorrhage. | 2 | |||

| Diffuse traumatic brain injury without loss of consciousness. | 4 | |||

| Contusion and laceration of cerebrum, unspecified, without loss of consciousness, initial encounter. | 2 | |||

| Fracture of thoracic vertebra. | 1 | |||

| Multiple fracture of ribs, right side, initial encounter for open fracture. | 1 | |||

| Multiple fracture of ribs, unspecified side, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Wedge compression fracture of first lumbar vertebra, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Multiple fracture of pelvis without disruption of pelvis ring | 2 | |||

| Fracture of pubis. | 1 | |||

| Nondisplaced fracture of anterior wall of right acetabulum, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Fracture of other parts of pelvis, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Laceration of liver, unspecified degree, initial encounter. | 1 | |||

| Fracture of clavicle. | 1 | |||

| Fracture of unspecified part of scapula, left shoulder, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified fracture of upper end of left humerus, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified open wound of right elbow, initial encounter. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified fracture of shaft of right ulna, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Traumatic rupture of left radial collateral ligament. | 1 | |||

| Displaced intertrochanteric fracture of left femur. | 1 | |||

| Displaced comminuted fracture of right patella. | 1 | |||

| Displaced bicondylar fracture of left tibia, initial encounter for closed fracture. | 1 | |||

| Sprain of posterior cruciate ligament of right knee, initial encounter. | 1 | |||

| Tear of anterior cruciate ligament of right knee, initial encounter. | 1 | |||

| Unspecified multiple injuries. | 1 | |||

| Disruption of wound, unspecified. | 2 | |||

| Infection and inflammatory reaction due to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube. | 1 | |||

| U00-U85 | Codes for special purposes. | Coronavirus infection, unspecified. | 9 | 9 (1.72) |

| V00-Y99 | External causes of morbidity. | Person injured in unspecified motor-vehicle accident, traffic. | 1 | 1 (0.19) |

| Z00-Z99 | Factors influencing health status and contact with health services. | Acquired absence of right great toe. | 1 | 15 (2.86) |

| Acquired absence of limb, unspecified. | 3 | |||

| Tracheostomy status. | 7 | |||

| Presence of prosthetic heart valve. | 1 | |||

| Coronary angioplasty status. | 1 | |||

| Dependence on respirator, status. | 2 |

| Type of antibiotic agent | Total prescribed number | Skin infection/ cellulitis and abscess/ gangrene/ ulcer/wound | Tuberculosis | Sepsis | Ear infection | CNS infection | URTI/LRTI | COPD | Pleural effusion | Pneumonia | Abdominal pain/dyspepsia | Abdominal abscess | Diarrhoea | Pancreatitis | UTI | Fracture/injury | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mupirocin | 2 (0.59) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Doxycycline | 4 (1.18) | 1 (25.00) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tigecycline | 5 (l·47) | 2 (40.00) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) |

| Ampicillin | 1 (0.29) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Flucloxacillin | 3 (0.88) | 2 (66.66) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Amoxicillin- clavulanic acid | 20 (5.91) | 11 (55.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.00) | 2 (10.00) | 1 (5.00) | 2 (10.00) |

| Piperacillin- tazobactam | 57 (16.86) | 9(15.87) | 0 (0) | 17 (29.82) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.75) | 15 (26.31) | 2 (3.50) | 2 (3.50) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.50) | 5 (8.77) | 3 (5.26) | 1 (1.75) |

| Cefuroxime | 25 (7.39) | 7(28.00) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.00) | 2 (8.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.00) | 2 (8.00) | 6 (24.00) | 2 (8.00) |

| Ceftriaxone | 51 (15.08) | 8(15.68) | 1 (1.96) | 4 (7.84) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.84) | 2 (3.92) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.92) | 13 (25.49) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.96) | 1 (1.96) | 0 (0) | 7 (13.72) | 4 (7.84) | 4 (7.84) |

| Ceftazidime- avibactam | 4 (1.18) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.00) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) |

| Cefepime | 3 (0.88) | 1 (33.33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.33) | 1 (33.33) | 0 (0) |

| Meropenem | 37 (10.94) | 4(10.81) | 0 (0) | 10 (27.02) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.70) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8(21.62) | 1 (2.70) | 1 (2.70) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.70) | 4 (10.81) | 4 (10.81) | 3 (8.10) |

| Ertapenem | 9 (2.66) | 2(22.22) | 0 (0) | 2 (22.22) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2(22.22) | 0 (0) | 1(11.11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.11) | 1 (11.11) | 0 (0) |

| Ceftolozane- tazobactam | 3 (0.88) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim | 2 (0.59) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Erythromycin | 1 (0.29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Azithromycin | 5 (1.47) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Clindamycin | 4 (1.18) | 3 (75.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) |

| Gentamicin | 2 (0.59) | 1 (50.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Amikacin | 2 (0.59) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8 (2.36) | 2 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Levofloxacin | 26 (7.69) | 2 (7.69) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.84) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.69) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.84) | 12(46.15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (19.23) | 2 (7.69) | 1 (3.84) |

| Moxifloxacin | 1 (0.29) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Vancomycin | 13 (3.84) | 1 (7.69) | 0 (0) | 5 (38.46) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.69) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.69) | 1 (7.69) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.69) | 1 (7.69) | 2 (15.38) |

| Teicoplanin | 6 (1.77) | 1 (16.66) | 0 (0) | 3 (50.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.66) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.66) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Colistimethate | 6 (1.77) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.33) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.66) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.66) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.66) | 1 (16.66) |

| Metronidazole | 11 (3.25) | 1 (9.09) | 0 (0) | 2 (18.18) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (9.09) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 2 (18.18) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 1 (0.29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Linezolid | 10 (2.95) | 1 (10.00) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10.00) | 2 (20.00) | 0 (0) |

| Rifampicin | 4 (1.18) | 0 (0) | 3 (75.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Isoniazid | 4 (1.18) | 0 (0) | 3 (75.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pyrazinamide | 4 (1.18) | 0 (0) | 3 (75.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ethambutol | 4 (1.18) | 0 (0) | 3 (75.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 338 | 63 (18.63) | 15 (4.43) | 60 (17.75) | 1 (0.29) | 13 (3.84) | 7 (2.07) | 1 (0.29) | 4 (1.18) | 61 (18.04) | 8(2.36) | 8(2.36) | 4 (1.18) | 9 (2.66) | 35 (10.35) | 29 (8.57) | 20 (5.91) |

Cite this article

Menon V, Hussain MW, Molugulu N. Prescribing Pattern of Antibiotics among Hospitalized Geriatric Patients at a Private Academic Health System in the United Arab Emirates. J Young Pharm. 2024;16(1):102-14.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Gulf Medical University and Thumbay University Hospital for the constant support and encouragement.

ABBREVIATIONS

| ATC | Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical |

|---|---|

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| EML | Essential Medicines List |

| GCC | Gulf Corporation Council |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| INRUD | International Network for the Rational Use of Drugs |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Harman D. The aging process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(11):7124-8. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Bajorek B. Defining ‘elderly’ in clinical practice guidelines for pharmacotherapy. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):489 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- The national policy for senior Emiratis. The official portal of the UAE government [internet]. [cited Oct 25 2022]. Available fromhttps://u.ae/e n/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/federal-governments-strategies-and-plans/the-national-policy-for-senior-emiratis

- Ageing and health [internet]. [cited Oct 25 2022]. Available fromhttps://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

- Regional profile of the Arab region demographic of ageing: trends, patterns, and prospects into 2030 and 2050 [internet]. [cited Oct 25 2022]. Available fromhttps://archive.unescwa.org/sites/www.unescwa.org/files/page_attachments/demographics-ageing-arab-region-final-en_0.pdf

- Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice [internet]. [cited Oct 25 2022]. Available fromhttps://books.google.ae/books?id=p5Th5USEBYwC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0-v=onepage&q&f=false

- Communicable diseases bulletin [internet]. [cited Oct 25 2022]. Available fromhttps://www.doh.gov.ae/-/media/977680F7B30045E2A9A934ECADE155BF.ashx

- Yadesa TM, Gudina EK, Angamo MT. Antimicrobial use-related problems and predictors among hospitalized medical in-patients in Southwest Ethiopia: prospective observational study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0138385 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Chem ED, Anong DN, Akoachere JKT. Prescribing patterns and associated factors of antibiotic prescription in primary health care facilities of Kumbo East and Kumbo West Health Districts, North West Cameroon. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(3):e093353 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse TY, Molla M, Yimer YS, Tarekegn BS, Kefale B. Evaluation of antibiotic prescribing patterns among inpatients using World Health Organization indicators: A cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2022;10:20503121221096608 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Bekele NA, Hirbu JT. Drug therapy problems and predictors among patients admitted to medical wards of Dilla University Referral Hospital, South Ethiopia: A case of antimicrobials. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:1743-50. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Dechasa M, Chelkeba L, Jorise A, Sefera B, Melaku T. Antibiotics use evaluation among hospitalized adult patients at Jimma Medical Center, southwestern Ethiopia: the way to pave for antimicrobial stewardship. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2022;15(1):84 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- El-Dahiyat F, Salah D, Alomari M, Elrefae A, Jairoun AA. Antibiotic prescribing patterns for outpatient pediatrics at a private hospital in Abu Dhabi: A clinical audit study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(12):1676 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Alneyadi AM, Alketbi L. Antibiotic prescription rates for upper respiratory tract infections at the Alain ambulatory healthcare centers, United Arab Emirates; 2014-2016. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Alemkere G, Tenna A, Engidawork E. Antibiotic use practice and predictors of hospital outcome among patients with systemic bacterial infection at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital: identifying targets for antibiotic and healthcare resource stewardship. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0212661 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla SN, Yousef BA. Prescribing patterns of antimicrobials in the internal medicine department of Ibrahim Malik teaching hospital in Khartoum, 2016. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;34:89 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi MQ, Salam M, Alqahtani FY, Ahmed AE, Alenaze AQ, Al-Jeraisy M, et al. An Evaluation of Antibiotics prescribing patterns in the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:3241-7. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Mohajer KA, Al-Yami SM, Al-Jeraisy MI, Abolfotouh MA. Antibiotic prescribing in a pediatric emergency setting in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011;32(2):197-8. [PubMed] | [Google Scholar]

- Oqal MA, Elmorsy SA, Alfhmy AK, Alhadhrami R, Ekram R, Althobaiti I, et al. Patterns of antibiotic prescriptions in the outpatient department and emergency room at a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2015;3(2):124 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yamani A, Khamis F, Al-Zakwani I, Al-Noomani H, Al-Noomani J, Al-Abri S, et al. Patterns of antimicrobial prescribing in a tertiary care hospital in Oman. Oman Med J. 2016;31(1):35-9. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Aly M, Balkhy HH. The prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in clinical isolates from Gulf Corporation Council countries. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1(1):26 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Demoz GT, Kasahun GG, Hagazy K, Woldu G, Wahdey S, Tadesse DB, et al. Prescribing pattern of antibiotics using WHO prescribing indicators among inpatients in Ethiopia: A need for antibiotic stewardship program. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:2783-94. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- World health organization. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in health-care facilities in low- and middle-income countries: a WHO practical toolkit. 2019:30-60. (Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO) [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels I, Versporten A, Drapier N, Vlieghe E, Goossens H. Hospital antibiotic prescribing patterns in adult patients according to the WHO Access, Watch and Reserve classification (AWaRe): results from a PPS survey in 69 countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(6):1614-24. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ingelbeen B, Koirala KD, Verdonck K, Barbé B, Mukendi D, Thong P, et al. Antibiotic use prior to seeking medical care in patients with persistent fever: A cross-sectional study in four low- and middle-income countries. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(9):1293-300. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ravi G, Chikara G, Bandyopadhyay A, Handu S. A prospective study to evaluate antimicrobial prescribing pattern among admitted patients in hilly Himalayan region of northern India. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2021;10(4):1607-13. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ntšekhe M, Hoohlo-Khotle N, Tlali M. Antibiotic prescribing patterns at six hospitals in Lesotho Published for the US Agency for International Development by the Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems Program. 2011 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Patel J, Deshpande S. Assessment of antibiotic prescribing pattern using World Health Organization prescribing indicators in a tertiary care hospital, Gujarat. Int J PharmSci Invent. 2020;9:17-22. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Atif M, Sarwar MR, Azeem M, Umer D, Rauf A, Rasool A, et al. Assessment of WHO/ INRUD core drug use indicators in two tertiary care hospitals of Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2016;9(1):27 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Amaha ND, Berhe YH, Kaushik A. Assessment of inpatient antibiotic use in Halibet National Referral Hospital using WHO indicators: A retrospective study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):904 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AM, Awad AI. Drug use practices at pediatric hospitals of Khartoum State, Sudan. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(12):1986-93. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Mudenda W, Chikatula E, Chambula E, Mwanashimbala B, Chikuta M, Masaninga F, et al. Prescribing patterns and medicine use at the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia. Med J Zamb. 2016;43(2):94-102. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Mugada V, Mahato V, Andhavaram D, Vajhala SM. Evaluation of prescribing patterns of antibiotics using selected indicators for antimicrobial Use in Hospitals and the Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) classification by the World Health Organization. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2021;18(3):282-8. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Gutema G, Håkonsen H, Engidawork E, Toverud EL. Multiple challenges of antibiotic use in a large hospital in Ethiopia- A ward-specific study showing high rates of hospital-acquired infections and ineffective prophylaxis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):326 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Yimenu DK, Emam A, Elemineh E, Atalay W. Assessment of antibiotic prescribing patterns at outpatient pharmacy using World Health Organization prescribing indicators. J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:2150132719886942 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Erbay A, Bodur H, Akinci E, Colpan A. Evaluation of antibiotic use in intensive care units of a tertiary care hospital in Turkey. J Hosp Infect. 2005;59(1):53-61. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ayele F, Engidawork E, Seboxa T. Drug use evaluation of third generation cephalosporins in the internal medicine wards of Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital. Addis Ababa University. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Sileshi A, Shibeshi W, Tenna A. Evaluation of ceftriaxone utilization in the medical and emergency wards of TASH, Addis Ababa University. Int J Clin Pract. 2023:8074413 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Strengthening pharmaceutical systems. Published for the U.S. Agency for International Development by the strengthening pharmaceutical systems program. 2012 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Bansal D, Mangla S, Undela K, Gudala K, D’Cruz S, Sachdev A, et al. Measurement of adult antimicrobial drug use in tertiary care hospital using defined daily dose and days of therapy. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2014;76(3):211-7. [PubMed] | [Google Scholar]